JANUARY 12, 2010 — Before I tell the story of how Santa Claus ended up hiking in the Grand Canyon this December, I suppose I must tell the Story of My Santa Suit. The story begins with me buying the world’s cheapest Santa Claus costume — one made of thin felt, with no beard and fake leather pieces that supposedly make normal shoes look like Santa’s boots — in an attempt to entertain guests at my Christmas party in early December. Strangely, when my sister Jen saw the resulting photos of (sometimes reluctant) partygoers sitting on my lap (thanks, Facebook), she demanded that I stage an encore performance of my unconvincing Santa at her Christmas Eve party for her neighborhood’s kids. Always willing to embarrass myself, I covertly climbed up onto the high porch of her backyard tree house in Orange County on Christmas Eve, hid behind a forest of palm fronds, and loudly jangled a garland of sleigh bells. Immediately, my six- and seven-year-old nephews, as well as ten other children, came running outside the house to see Santa. The children yelped with delight when they caught a glimpse of me, dressed as Saint Nicholas, hiding behind the trees high above them. I was amazed that my seemingly magical suit enchanted the kids so easily. Nevertheless, my strained rendition of “Ho! Ho! Ho!” prompted my brother-in-law to exclaim, “Uh, oh. Santa’s angry.” I tried.

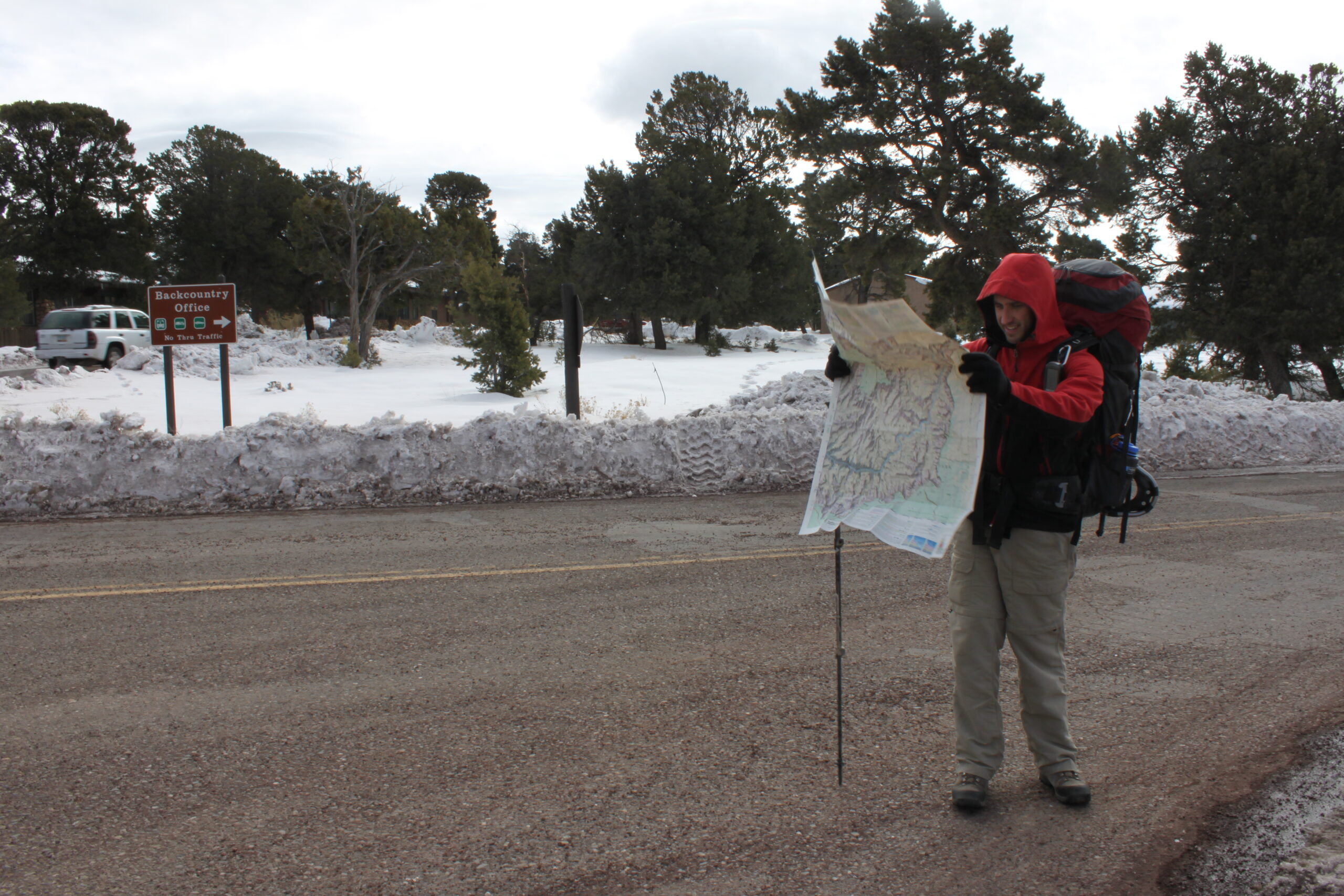

Hank discusses an itinerary with a Grand Canyon Park Ranger at the Backcountry Information Center.

Just a few days after my not-even-close-to-Golden-Globe-winning Santa performance, my brother Brian and I threw our backpacking equipment, as well as the Santa suit, into my car, and we began driving across the Arizona desert toward the Grand Canyon. We have a history of seeking out the world’s best hiking expeditions, then figuring out how we can amp up their difficulty and danger levels, to turn them into true adventures. On Vancouver Island’s West Coast Trail, we jumped across hazardous surge channels and raced against high tides on our way to Michigan Beach. In Torres del Paine National Park in Chilean Patagonia, we tackled two side trips, 21 additional miles in pouring rain and snow, in addition to the typical park loop. When we traveled to Alaska’s Denali National Park to hike to McGonagall Pass, we escaped from a freezing glacial river and then added a 15-mile detour across an almost impassable glacier. So, when we decided to take on the Grand Canyon’s iconic rim to rim to rim hike — which demands that hikers trek from the South Rim of the Canyon, down to the canyon floor, up to the top of the North Rim, and then back again — we wondered what we might be able to do to make our fantastic hiking plans even more fantastic. (After all, we have friends who believe that our secret motto is, “Whoever dies on the craziest, most dangerous adventure, wins,” and we never want to disappoint them.)

We had already encountered difficulty trying to embark on this particular hike. Backcountry hiking in the Grand Canyon is famously popular, and hikers who want reservations must apply by FAX four months in advance. I sent FAXs three separate times, and each time, the National Park rejected our application because other hikers managed to beat us to it. It’s also possible to simply show up at the Grand Canyon in an attempt to nab a small number of last-minute permits, but during the ideal hiking season, last-minute hikers often have to wait for days before starting their hike. But then, an idea dawned on me: if we attempted the hike outside the ideal season, in late December, we would have almost no competition for permits, because deep snowdrifts and sub-freezing temperatures on the North Rim’s North Kaibab Trail make the hike all but impossible that time of year.

In early December, I decide to call the Grand Canyon’s Backcountry Information office to run my idea past the Park Ranger.

“Well, you won’t be able to get up to the North Rim,” she says. “It’s closed, and you’ll risk hypothermia if you try to hike through the deep snow up there.”

“What if we carry snow shoes?” I ask.

“That might help,” she says. “But it would still be extraordinarily difficult. No one has been up there in a month. “

That’s all I need to hear. Soon, I’ve convinced Brian to buy two shiny new pairs of Atlas 925 snowshoes with me, and we’ve resolved to hike to the North Rim and back.

At 3:00 AM on the morning after leaving Orange Country, we arrive at the world’s most famous hole in the ground. After only four hours of sleep, we show up at the Grand Canyon’s South Rim Backcountry Information Center at 7:58 AM, where we’re greeted by a gaggle of other eager hikers holding priority numbers, assigned to them the day before. We don’t yet have a number, so things don’t look good for us. While we’re waiting, three twenty-something guys in sunglasses and hoodies, who look like they’ve just came from a surfing competition, get out of a big RV and join us in line.

Hank’s backpack weights 45 pounds.

“What are we waiting for?” one of them says. “Is this the line to the Grand Canyon?”

My brother and I helpfully point them toward the huge, adjacent void in the desert.

Finally, after all of the number-holders receive permits, the Park Ranger tells us that a few remain. We tell her that we want to hike to the North Rim.

“You’ll never make it. The snow’s too deep,” she says. “Also, this morning, a water main burst on the trail to Cottonwood Camp. We closed the route because we think the trail may break off the side of the Canyon, and there won’t be any drinking water past that point.” Apparently, being a Park Ranger means being a professional discourager.

We explain our ambitious snowshoeing plan to her, adding in details of our extensive trekking experience, and she backs down. Reluctantly, she enters the details of our planned 5-day, rim-to-rim-to-rim snowshoeing itinerary into the park’s archaic computer system.

(Note: There are hikers who manage to hike from rim to rim (and sometimes back) in one or two days. If you’re a glutton for punishment and a talented athlete, such a trip is possible, though only by traveling in ideal temperature and snow conditions and not carrying a backpack with heavy camping equipment. But to properly savor and enjoy this adventure, hikers should set aside at least four, and preferably six, days for this trip. Considered to be one of the most dangerous hikes in America, this trek has left many people injured or dead in the Canyon due to poor trip planning and unforgiving weather conditions.)

The lobby of the Grand Canyon South Rim’s El Tovar hotel.

By the time we leave, she begins encouraging us — I assume because, at this point, there’s no reason for her to be honest about what she thinks will happen. She doesn’t want any of her gloomy predictions to end up becoming true.

“No one has been up there since November,” she calls out as we leave. “But if you make it, let us know what it’s like up there!”

In the parking lot of the Backcountry Information Center, we pull our 45-pound backpacks out of my car’s trunk, and I notice my Santa suit, still sitting in the trunk from my sister’s Christmas Eve party. In a sudden moment of inspired whimsy, I stuff the bright red jacket and pants into my backpack. Admittedly, this action is an enormous protocol violation, because Brian and I normally weigh and mutually approve every item that goes into our backpacks to minimize weight.

“Really?!” Brian asks with a strong dose of sarcasm.

In the El Tovar Hotel’s white-table clothed dining room overlooking the Canyon’s South Rim, Brian and I order El Tovar’s Pancake Trio: a plate of buttermilk, blue cornmeal, and buckwheat pancakes. While we wait for the food, my brother writes a postcard to his girlfriend in an affected voice intended to give the impression that we’re colonial explorers, discovering the Grand Canyon for the time:

“It hath been over a fortnight since last I wrote,” Brian scrawls. “The road west tests a man to his very limit. Hank has been struck with typhoid. A kind Navajo healer has done all he can, but he told us that the only chance we have is to continue to a mysterious, awe-inspiring place called the Great Gash of Awe. We’re calling it the Aweful Canyon. We’re still working on the name.”

Soon, our waiter arrives with our matching breakfasts and a saucière of bright pink prickly pear syrup.

“This is prickly pear syrup, which is the syrup that the chef paired with these pancakes,” he says nervously. Then he pauses for about 10 seconds, looking at us, as though he’s challenging us to beg for normal syrup. We get the impression that he’s had previous problems selling his diners on the neon goo — or maybe he doesn’t think we look sophisticated enough to handle a radioactive-looking pancake topping.

What he doesn’t know is that my brother and I will try anything. He doesn’t know that we’re carrying snowshoes, a Santa suit, and an endless yearning to do the impossible. He doesn’t know that his prickly pear syrup is the least risky thing we’ll try during the next five days, during our mission to hike the Grand Canyon in winter, rim to rim to rim.

We slather our pancakes with the syrup, and quickly, we’ve cleaned our plates.

Hiking in Santa Claus’s bright celebrity spotlight

Trekking the Grand Canyon as Saint Nicholas turns out to be a full time job.

JANUARY 14, 2010 — Brian and I are walking briskly across a parking lot, our stomachs filled with pink syrup, when we realize that we have no idea where the trailhead for the Bright Angel Trail into the Grand Canyon is located. I unfold our topographical map in an attempt to find the huge, one-mile deep hole in the ground that we know is less than 500 feet from us. Suddenly, the group of surfer-looking guys that we met at the Backcountry Information Center seem slightly less ridiculous.

Santa Claus (a.k.a. Hank) walks down Bright Angel Trail into the Grand Canyon.

Standing dumbfounded on the asphalt, gazing, bewildered, at a huge backcountry map, Brian and I look like the world’s most inexperienced hikers. We laugh at ourselves — not because the scene is ridiculous, though it is — but because we’ve gotten lost, just like this, within the first ten seconds of every major hike we’ve ever embarked upon. By now, it’s tradition. If we ever know where we’re going at the beginning of a trek, then I’ll worry.

But soon, we’re standing on a precipice looking into a gigantic crevice, over one mile deep, 277 miles long and 18 miles wide, amazed by the expanse of snow-covered, 2-billion-year-old rock striations. The dazzling range of rock colors: brick reds, copper oranges, sunflower yellows, sky blues, and deep purples prompts us to take a moment before starting down the trail.

Hank searches for the Grand Canyon’s Bright Angel Trailhead on a topographical map.

“It truly is ‘aweful,'” I say.

Brian tries to take a picture of the landscape, but our wide-angle lens totally fails to capture the spectacular vista.

“It’s just too Grand,” my brother jokes.

“Too Grand,” I agree.

Soon, we’re hiking down Bright Angel Trail, a path filled with families and couples taking short day hikes on the Park’s least steep route into the Canyon. With so many people near the Canyon’s South Rim, I decide that this is the perfect time to don the Santa suit that I shoved into my backpack in the parking lot. I stop on a snowy ridge and quickly put on the costume over my jacket and synthetic pants. When I add my backpack over the suit, I’ve become Santa Claus: Outdoor Adventure Edition.

Bizarrely, as we make our way down the snow-covered trail toward the Canyon floor, I seem to fit in perfectly with the wintery backdrop while also looking totally out of place. I’m surprised to discover that wearing a bright red and white felt suit turns me into a totally different person. I start yelling “Ho, Ho, Ho!” and “Merry Christmas!” to every hiker we pass on the snowy trail. As the trip continues, Brian and I begin alternating the Santa suit between us. We discover, to our delight, that the costume casts a magic spell over the other hikers too. Families, couples, and even hardcore outdoor adventurers not only become instantly happy and uncharacteristically friendly when we run into them, but they almost always treat us as though they believe that the one of us with the suit is the real Father Christmas.

Mules carry riders down the Grand Canyon’s Bright Angel Trail.

“Thanks for the presents, Santa!” many hikers say.

“I’ve been hiking here since 1976,” one woman tells Santa, “and this is the first time I’ve ever seen Santa Claus coming down the trail.”

“Can I take a photo of you and my wife?” a surprising number of men ask Santa.

Children simply stare at Santa in awe. One teenage girl takes one look at Santa hiking down the trail and says, simply: “Awesome.” Tourists riding mules laugh when Santa shouts, “Have a Happy New Year!” as they pass. A 10-year-old boy, first unimpressed by Santa’s appearance, becomes enraptured when Santa reveals his ambitious plan to hike to the North Rim and back.

Hikers stand in a rock tunnel on the Grand Canyon’s Bright Angel Trail.

As we continue down the trail, we start to realize that constantly staying in character is exhausting. “I feel like I need to be ‘on’ all the time,” I complain to Brian. Soon, we begin cataloging a repertoire of witty responses, so that we’re always prepared for other hikers’ clever remarks. We feel like we’re in a Santa role-playing arms race.

“Aren’t you hot in that suit, Santa?” one hiker asks. “Of course not! My suit is magic, and I have 365 of them in my closet — one for every day of the year!” I respond.

“Santa, what are you doing here in the Grand Canyon?” another queries. “My sleigh broke down, and I’m hiking back to the North Pole,” Brian responds. “By the way, have you seen Blitzen? Or any of the other reindeer?”

A woman laughs as she spies Santa Claus approaching her on Bright Angel Trail.

“Santa, it’s a little late for Christmas,” a few criticize. “Trust me, I didn’t miss Christmas,” I respond. “I was working the whole night. Afterward, I always vacation in the US National Parks. They’re second to none.”

“Santa, I didn’t get what I wanted for Christmas this year!” many complain. “Well, I have my list, and I checked it twice,” Brian retorts. “I’m sorry, Santa. I’ll try better next year,” they apologize.

After a day of Santa banter, all the while taking photos with hikers, Brian and I arrive at the Indian Garden campsite, fatigued from the spotlight of Santa’s celebrity. When we erect our tent and settle in at our campsite, I take off the Santa suit so that we can relax and enjoy dinner.

A sign reminds hikers to be respectful of plants in the Grand Canyon.

But soon after, a friendly, 40-year-old blonde woman from Wisconsin rushes over to us. “What happened to your suit, Santa? It really raised my spirits! I loved it!” she gushes. “May I play you guys a song on my harmonica?”

As we cook dinner, she serenades us with “Red River Valley” — an old, lonely cowboy folk tune — while snow falls on us under the shadow of the Grand Canyon’s towering South Rim.

Come sit by my side if you love me Do not hasten to bid me adieu But remember the Red River Valley And the cowboy who loved you so true.

As we compliment her impressive musical talents, I realize that this is the first time ever that we have been offered a harmonica performance while backpacking. I realize that the red felt coat in my backpack is, indeed, somehow magical. It has a surprisingly powerful ability to bring people together and put smiles on their faces.

Hikers ask Brian to pose for a photo at Indian Garden.

With hopes that we’ll someday meet again, the woman with the harmonica asks for our e-mail addresses, which we write for her on a stray piece of a National Park brochure that she’s carrying with her. We write our contact information just above the Park Service’s slogan, which is printed on the paper. “Hank and Brian Leukart: Experience Your America,” it reads. She laughs.

Early the next morning, Brian puts on the Santa suit and goes to fill his Camelbak with water. A twenty-something-year-old woman interrupts him.

“Santa! Do you mind if I sit on your lap and get a picture?” she asks.

“Of course not,” my brother says. “It’s my job.”

We used to think that Santa worked only one night per year. Now, we know there’s no escaping Santa’s celebrity. It’s a full time job. But it’s an easy job to love.

How I came to believe in Santa Claus

Brothers face the hardest single trekking day of their lives, snowshoeing up the Grand Canyon’s North Rim.

JANUARY 22, 2010 — Brian and I start to doubt the magic of our Santa suit as frozen rain and snow pelts us relentlessly on the way to Cottonwood Camp at the bottom of the Grand Canyon’s North Rim. In the morning, we passed the location of the burst water pipe the Park Ranger had warned us about — which turned out to have caused little more than a deep puddle on the trail. But in the afternoon, as unforgiving winter weather worsened, we were forced to pack away the sopping wet, frozen Santa costume to avoid getting hypothermia. Now, in the shadow of the 8,060-foot high North Rim, we know that the easy part of our trek is over.

Brian looks up at the Grand Canyon’s North Rim on New Year’s Day, 2010.

After a sub-freezing night at Cottonwood, we wake early in the morning to find the zippers on our tent frozen shut and our rain fly covered in ice. After packing up our gear, we start hiking through snow on the North Kaibab Trail. At first, it’s not deep enough to require our snowshoes. We make our way up the snowy, narrow path, teetering precariously on the edge of Canyon ridges, looking down on swaths of blood-red boulders covered in blinding white snow and desert cacti. We’re thankful for a clear, sapphire sky and warm sunlight, a notable contrast from the sleet and snow of the previous day.

As we hike under a seemingly never ending lattice of oversized icicles, the snow on the trail gradually deepens, starting from two feet and eventually reaching five. We put on our snowshoes. Hiking to the top of the Grand Canyon’s North Rim with a heavy backpack is a draining feat in ideal conditions, but with huge snowdrifts, we discover that it’s a nearly impossible physical challenge. The embarrassing truth is that we’ve had fantasies of our snowshoes enabling us to glide effortlessly on the tops of the snow drifts, but they aren’t coming true — at all. The trail has been deserted for a month, and we find ourselves trailblazing through unpacked, very deep snow. In fact, our snowshoes seem useless — that is, until, we try taking them off and find ourselves immobilized, waist-deep in white powder. We put the snowshoes back on, preventing our feet from sinking more than a couple feet. Of course, the foot-sinking turns out to be only half the battle — immediately after each step, we must then pull our foot and snowshoe out of the sink hole — over, and over, and over, for miles, and miles, and miles.

Brian hikes on the snowy North Kaibab Trail below the Grand Canyon’s North Rim.

We come to another revelation: snowshoeing on an unused trail would be great fun with a group of eight people, but with only two, it’s a nightmare. The person in front doing the trailblazing, packing down the deep snow drifts, ends up working much, much harder than the person following in his footsteps. When I’m the trailblazer, I endure about twenty steps. Then, utterly exhausted, I turn around and announce that there is no chance we’ll ever make it to the top and insist that our mission is doomed to failure. Brian, following behind, insists, “No, we can definitely make it to the top! We just need to keep moving!” Then, he takes over as trailblazer. Twenty steps later, he announces that we’ll never make it to the top and begs me to give up the mission. We repeat this process, dozens of times, for three miles.

Brian looks at the snowy North Kaibab Trail.

When we reach the rock hole called Supai Tunnel, I am encouraged, because I remember from a previous North Kaibab Trail hike in autumn that even sixty-year-old grandmothers, in ideal conditions, were able to hike from Supai Tunnel to the top. As we pass through the Tunnel, I’m sure that Brian and I can be as strong as grandmothers. But on the other side of the Tunnel, we encounter ten-foot snowdrifts for the first time. Mule-typing posts, used most of the year as a resting area for tourist-carrying mules, barely peek out from the top of the snow drifts. The sun is setting. The temperature is plummeting. We’re clawing our way up the trail through the snow at less than half a mile per hour, on New Year’s Eve, 2009. We don’t see any grandmothers around. Father Christmas is nowhere to be found.

Brian reluctantly demonstrates the depth of the snow on the Grand Canyon’s North Kaibab Trail. Note that he is wearing snowshoes on both feet.

We both feel like we’d rather jump to our death from one of the Canyon’s ridges than do any more trailblazing. I, behind Brian, decide that our struggle is purely psychological, and I try to take over trailblazing. But, immediately, I feel like I don’t have enough energy to take one additional step in the deep snow, let alone the thousands more we need to take to get to the top. A beautiful purple and orange sunset, seen over the snow-covered walls of the Canyon’s rugged crags, soon gives way to almost total darkness. The temperature reaches zero degrees Fahrenheit. I feel something foreign stuck in my hiking boots, and then I realize that it’s simply my toes, which feel like they’re no longer part of my body, because they’ve gone completely numb. I turn around and look into Brian’s eyes in what feels like the least manly moment of our lives.

A sunset reflects on rocks over the Grand Canyon’s North Kaibab Trail.

“We can’t make it,” Brian says. “It’s too dark. It’s too cold. We need to stop.”

I know he’s right, but we’re only a mile and a half below the rim, and the idea of giving up is so dispiriting I can’t bring myself to say anything. In almost total silence, we pack down an area of snow with our snowshoes and erect our tent only feet from the edge of a 2,000-foot drop into the Canyon’s abyss.

In our tent, we put on every piece of clothing that we have, stuff chemical heat packs into our socks, and zip ourselves, like mummies, into our sleeping bags. We’re almost out of water, so we boil pots of snow to make dinner and rehydrate ourselves. Without discussing our plan much, I set my alarm to wake us up an hour before sunrise the next morning.

During the night, I wake to discover that the sleeping bag fabric on my skin is ice cold, and our water bottles are frozen solid. It’s the coldest night we have ever spent camping. I step outside the tent and find myself blinded by the intensely bright light of a full moon bouncing off the snow in the Canyon. I begin shivering immediately and uncontrollably. When I get back in the tent, Brian tells me he needs to go to the bathroom. I’m about to warn him about the conditions outside when he disappears. He’s gone for about sixty seconds and then stumbles back into the tent, shivering and looking he has just escaped a ten-day stint trapped in a meat freezer.

Santa Claus (a.k.a. Hank) and Brian celebrate on the Grand Canyon’s North Rim.

“DO. NOT. GO. OUT. THERE.” he says. “Seriously. I’m totally blind. I can’t feel my skin. Promise me that we will never, ever go snowshoeing again.”

“I know,” I say. “I know.”

I start drifting back to sleep. I’m halfway between being awake and unconsciousness when I think I see our red Santa Suit, crumpled in a ball in the tent’s vestibule, covered in frost and shimmering in the moonlight, doused in pink, prickly pear syrup. Visions of me and Brian, celebrating on the Grand Canyon’s North Rim on New Year’s Day morning wearing the Santa Suit, dance through my head.

Santa Claus (a.k.a. Brian) looks out at the Grand Canyon from the South Kaibab Trail.

I realize that, the next morning, our magical Santa suit will get us to the top.

When our wakeup alarm sounds, we reluctantly get out of our sleeping bags, only to discover that our previously wet hiking boots have become frozen blocks of ice. They are so frozen solid that we can’t even get our feet halfway into them. We fire up the stove, and I pour a pot of boiling water onto my boots. After they thaw a bit, I manage to shove my feet into them. Quickly, they refreeze, and my feet feel like they’re trapped in blocks of ice, locked in a freezer, inside a tub of ice cream, on the North Pole.

We forego breakfast, pack small daypacks, and decide that we’re going to take one last shot to get to the North Rim, this time without our 45-pound backpacks weighing us down. Seconds before we leave our camp, the Santa suit catches my eye, and I shove it into my daypack.

Though our final ascent to the North Rim feels even more arduous than the day before, I push forward, remembering my New Year’s Eve dreams. When we reach an area under a canopy over Engelmann Spruce trees, I tell Brian that the area seems familiar to me. Then we see it: the “Coconino Overlook” sign, almost completely buried in snow. It’s a sign that I have seen, on a previous hike in the Canyon without snow, and I know that we’re less than three-quarters of a mile from the top.

A view of the Grand Canyon’s snow-covered South Kaibab Trail

“We can make it now,” I announce, feeling barely sure.

Ignoring the pain in our legs, we continue toward the top, with 100-foot spruce trees towering over us and huge swaths of snow in every direction. I’m leading us up an incline, when I spot the North Kaibab Trailhead sign, 50 feet ahead of us. It looks about a quarter tall as the last time I saw it, because the snow is so deep.

“We made it! Happy New Year! We did it! Happy New Year!” we yell, over and over. We’re exhausted and relieved, giddy and ecstatic. We take turns putting on the Santa suit, posing for New Year’s Day photos on the Grand Canyon’s North Rim.

Then, together, we take one last look at the gorgeous, snowy Canyon view before heading back down, toward the South Rim again.

“It’s just too Grand,” Brian says quietly.

“Too Grand,” I agree.

I don’t think I’m too old to say it. I believe in Santa Claus.

How to Hike the Grand Canyon Rim to Rim to Rim

Visit the Grand Canyon National Park Backcountry Permit information site to learn how to apply for a permit. You should FAX the Backcountry Permit Request Form four months in advance of your planned hiking dates to give you the highest chance of receiving a permit.

The best months to hike the Grand Canyon are March through May and September through November, because temperatures on the Canyon floor can exceed 100 degrees Fahrenheit during the summer. Unfortunately, those months are also the most difficult months to obtain permits. All North Rim services are closed mid-October to mid-May, and hiking to the North Rim without snowshoes (and even with them) is extremely difficult during the winter months.

You can also simply show up at the Backcountry Information Office to attempt to get a last-minute permit, but due to the waitlist process, it’s likely that you’ll have to wait at least two to three days before starting your hike during the typical Grand Canyon hiking season (March through November).

The Grand Canyon South Rim, usually the starting point for rim to rim to rim hikes, is located in northern Arizona. It’s a two hour drive from Flagstaff, a four hour drive from Phoenix, and a six hour drive from Las Vegas.

SIX-DAY ITINERARY: This itinerary lets you savor the Canyon and prevents you from having to complete more than one rim ascent or descent in a single day. Descending South Kaibab Trail makes more sense for most people because, as compared to Bright Angel Trail, it’s significantly steeper and its expansive views are more scenic. Then, hikers can return by way of the less grueling Bright Angel Trail.

South Kaibab Trailhead to Bright Angel Camp

Bright Angel Camp to Cottonwood Camp

Cottonwood Camp to the North Rim Campground

The North Rim Campground to Cottonwood Camp

Cottonwood Camp to Bright Angel Camp

Bright Angel Camp to the Bright Angel Trailhead

FOUR-DAY ITINERARY: This short itinerary is for experienced hikers but still prevents you from having to complete more than one rim ascent or descent in a single day.

South Kaibab Trailhead to Cottonwood Camp

Cottonwood Camp to the North Rim Campground

The North Rim Campground to Bright Angel Camp

Bright Angel Camp to the Bright Angel Trailhead

TWO- OR ONE-DAY ITINERARY: It is possible to do this hike in two days (or even one day) in ideal weather conditions (April and October) without a backpack. The advantage of doing this is that you won’t need a backcountry permit, but you won’t get to savor your journey much and you’ll probably be starting and ending your days by hiking for hours in the dark. You’ll also need a hotel reservation on the North Rim since you won’t be carrying a tent. Only the fittest hikers should try this stunt:

South Kaibab Trailhead to North Rim Campground

North Rim Campground to Bright Angel Trailhead

ONE-WAY ITINERARY: If a rim-to-rim-to-rim hike seems like more than you’re ready to sign up for, you can always try a shorter rim-to-rim hike. For $80 per person, Transcanyon Shuttle will take hikers on the 4.5 hour drive from one rim to the other. You can also try exchanging car keys with someone you see in the Canyon and arranging a meeting point or dividing your hiking group into two groups, starting at opposite rims.

View the route below or download the Without Baggage Grand Canyon Rim to Rim to Rim GPS track in GPX or KML format. Note that GPS devices only work intermittently on the Canyon floor.

Ha, awesome — Santa Claus hiking the Grand Canyon! My friend and I hitch hiked across the US, dressed as Catholic Monks, which was a blast. Loved reading about the responses people gave you on the trail.

Wow! What an achievement. I'm impressed – and a bit envy of you that could manage such adventure. Love your photos too – awesome to put it mildly.

Hey Hank. Great site. Enjoyed the candid writing. My husband and I are on a yearlong road trip——a honeymoon of sorts. He's threatening to take me on a rim-to-rim hike. I was going to forward your URL, but now I'm going to hide it, or he'll have me trudging through the ice in a few days. We're "chilling out" in Kenab, UT right now. Keep up the good work and feel free to check out our blog. We're open to suggestions and travel tips.

Jill

Jill: It sounds like you guys are embarking on an awesome adventure! Unless you're very experienced with this kind of thing, have snowshoes, and are prepared for a world of hurt, I don't recommend a rim-to-rim in winter. At least, know what you're getting yourself into. But, if you want to do the Grand Canyon, I recommend doing a simpler loop, going down South Kaibab Trail, staying at Phantom Ranch/Bright Angel Camp, and then returning up Bright Angel Trail. You can do this in two days, or you can add some extra days day hiking around Phantom Ranch in the Canyon.

Kanab is adjacent to some of the best outdoors adventures in the world, by the way. You can hike to The Wave, Buckskin Gulch, or The Dive; you can go kayaking on Lake Powell; or checkout Kodachrome Basin State Park or Zion National Park. There's nothing there that's not beautiful. Have fun!

Amazing story! Your writing style is so engaging that I felt like I was there. My first backpacking trip ever was a snow camping trip where it hit -5 degrees the first night. We had to snowshoe in, and luckily it was a group of about 8 people (and I managed to stay towards the back). What you guys achieved is impressive, and hope you have many more adventures planned!

My 60-year-old wife and I just returned from a rim-to-rim-to-rim transcanyon hike earlier this month. Of course, our weather on the north rim was much milder. Loved seeing what it looked like on New Year's Day. Of course, my wife got a chuckle out of your comment that even a "60 year old grandmother" could make it as far as the Supai Tunnel.

Leroy: I'm glad you enjoyed the hike! The scenery is fantastic, and I'm inspired that anyone 60 years old can complete the hike! I hope I can at that age.

Very beautifully said.

Hank, your adventures are a great read, your photos are beautiful and tell a great story, I appreciate your blog, thank you.

My wife and I met at Ribbon Falls at the bottom of the Grand Canyon – 26 years ago. I was on a rim to rim marathon – did it in just under 5 hours – and she was backpacking from rim to rim. Said hello – she took a pic of us and we continued our run. Six months later we bumped into each other again as I was training for the Pikes Peak Marathon running up a mountain in Phoenix, and the rest, as they say is history. So the Grand Canyon rim to rim run or hike is one of our favorites and we have done it many times. Thanks for the memories. Wayne

Hiking is a great way to have fun.

Thanks for sharing this blog with us