SEPTEMBER 14, 2011 — It’s the day after the Japanese New Year, 2011, and I’m standing on Jingu Bridge, outside the Harajuku subway station, looking toward the entrance of Tokyo’s famous Meiji Jingu Shrine, amidst a sea of tens of thousands of Tokyo residents. We’re all walking together, in a surprisingly orderly fashion, through the torii, the Shinto shrine’s traditional Japanese gate. I’m the only person who’s not Japanese. I’ve only been in Japan for one night so far, but I’ve already learned that everyone in Japan always seems to know exactly where they’re going and what they’re doing. Tokyo seems like a place where everything always runs perfectly: the subway trains are always on time and the city’s streets are impeccably clean. In comparison, New York seems like a half-assed attempt at a city. So, I keep following the crowd, trusting that they’re not going to steer me wrong.

A map of the Tokyo subway system.

I have taken the subway’s Yamanote Line here because my guidebook suggests that I try to get a glimpse of cosplay girls — Japanese teenage girls who express their individuality outside of school by congregating on Jingu Bridge, wearing goth makeup, and dressing like Japanese anime and manga characters. I’m conflicted, because, while I’m dying to snap a few of my own photos of the Harajuku girls that have become iconic of Japanese culture, I’m also worried that I’ll be inadvertently contributing to a creepy rebelling-teenage-girl-zoo atmosphere. But, as I look around, I realize that my worries about my bizarre photo safari are irrelevant, because there are no cosplay girls to be found. Instead, I’m enveloped by a black and gray mob (it’s rare that I see anyone in Japan wearing any colors other than black or gray) heading toward the Shrine.

Thousands of Tokyo residents enter Meiji Jingu Shrine during the Japanese New Year.

The crowd is so dense that I’m afraid that if I stop moving, I will be trampled, so I keep moving, passing sake barrels with inscrutable Japanese characters on them. I am confused. Why are all these people here and what’s going to happen?! I wonder. Worried that I’ll be expected to partake in a mysterious, ancient Japanese tradition — a tradition that ends in me being sacrificed for being the only clueless gaijin (non-Japanese person) here — I start searching frantically for information on my phone about how to behave at a Japanese shrine. I discover that it’s traditional for Japanese people to visit a shrine during the first week of January. Then, I find the shrine’s web site, which, says that over three million people visit Meiji Jingu during the Japanese New Year, which explains the large crowd. I also find a series of ridiculous stick-figure diagrams, with an explanation that says that when I enter the shrine, I must wash my left hand, right hand, mouth, and left hand again at a wash basin. Then, I must wash the water ladle, ring a bell, throw coins into an offering box, bow twice, clap twice, make a wish, and then, finally, bow again. I also read that, when I’m done, I’ll get an omikuji, a strip of paper with a written fortune predicting my life outlook for the coming year. The whole thing seems a bit silly, but I feel relieved that these illustrated instructions will allow me to avoid a major cultural faux pas.

A Japanese boy sits on his father’s shoulders, waiting to enter the Meiji Jingu Shrine.

Still, I am totally bewildered, and, as I approach the wall of policemen directing traffic into the shrine, my stress level doubles. How can I be expected to remember all of these tasks? Wait, do I bow once or twice before I clap? And do I clap once or twice? And will the offering box accept American currency?! And can I wish for unlimited wishes? Is that even allowed? And what if my omikuji tells me that no one will ever love me again?! THEN WHAT?!

Japanese police manage the Meiji Jingu Shrine’s many visitors.

I’m preparing to run as fast as I can away from the shrine into the surrounding forest when a policeman looks straight at me. I’m terrified that he knows that I’m an imposter who has ended up here by accident, and I’m sure that he’s going to subject me to a two hour Shrine Visitation Test before letting me enter. Thankfully, though, after looking disapprovingly at my blue shirt and backpack, he waves me through the gate. I’M PRACTICALLY JAPANESE! I think, excitedly. But, I’m reminded once I’m inside the shrine and see everyone staring at my towering height and blue eyes that no one has mistaken me for a worshipper of Shinto. LOOK, DISAPPROVING PEOPLE, I DIDN’T EVEN COME HERE INTENTIONALLY, I yell. I WAS TRYING TO GET SOME PHOTOS OF SOME REBELLIOUS TEENAGE GIRLS, SO CHILL OUT. Actually, I’m only yelling this in my head, to avoid being arrested for being the world’s creepiest creep.

A woman uses a wooden box filled with random numbers to determine which omikuji she’ll receive.

I follow the mob to a parking lot-sized offering area in front of the shrine’s main building. Already, I realize, I’ve failed, because the impenetrable crowd has made it impossible for me to get to the temizuya, the basin at which I’m supposed to wash myself. I took a shower this morning, I say to myself, trying to rationalize my behavior. I realize that others seem to have skipped this step too, and I hope that the Shinto Gods only enforce this rule on less crowded days at the Shrine. When I reach the front of the crowd, I watch as hundreds of people — adults, teenagers, and children — throw coins into the offering area, make wishes, bow, and clap. Feeling about as self-conscious as the first time I went to my first high school party, I join in by bowing, clapping, making a wish, and bowing again. I feel relieved that I haven’t made a total fool of myself — unless I have. I have no idea.

A woman hangs a folded omikuji on a wire fence.

Afterward, I join everyone else by lining up in front of workers wearing white robes, unsure of what I’ll be subjected to next. I comfort myself by remembering that mimicking the rest of the crowd has worked pretty well up until this point. When I get the front of the line, I give the white-robed woman a five-yen coin, and she hands me a mysterious wooden box with Japanese characters on it. I see a woman next to me turn her box over, so I do the same. A small wooden dowel with a number on it slides out, and the white-robed woman gives me a corresponding piece of paper covered in Japanese writing. I’ve done it! I think. I’ve obtained my first omikuji!

I ask the woman next to me to help me read my omikuji. Her English is not good, but she translates for me as best she can.

“You’re on the cusp of a needle, or on top of an orange,” she tells me. “There will be life paths with hurdles, but the right path will come, and when it does, you must have faith and move forward. It will lead you to uncivilized heaven, so expand that path, raise culture up, cut through the hurdles, and go forth.”

“Uh, okay. Is it a good fortune?” I ask her.

“Yes, it is good,” she says solemnly.

“How was yours?” I ask her, trying to be polite.

She shakes her head and looks down at the ground. She seems genuinely worried, and I think to myself that she may be taking the proceedings a bit too seriously, considering that omikuji are simply random, pre-printed fortunes. I watch her walk toward a fence made up of long, metal wires, covered with thousands of folded omikuji.

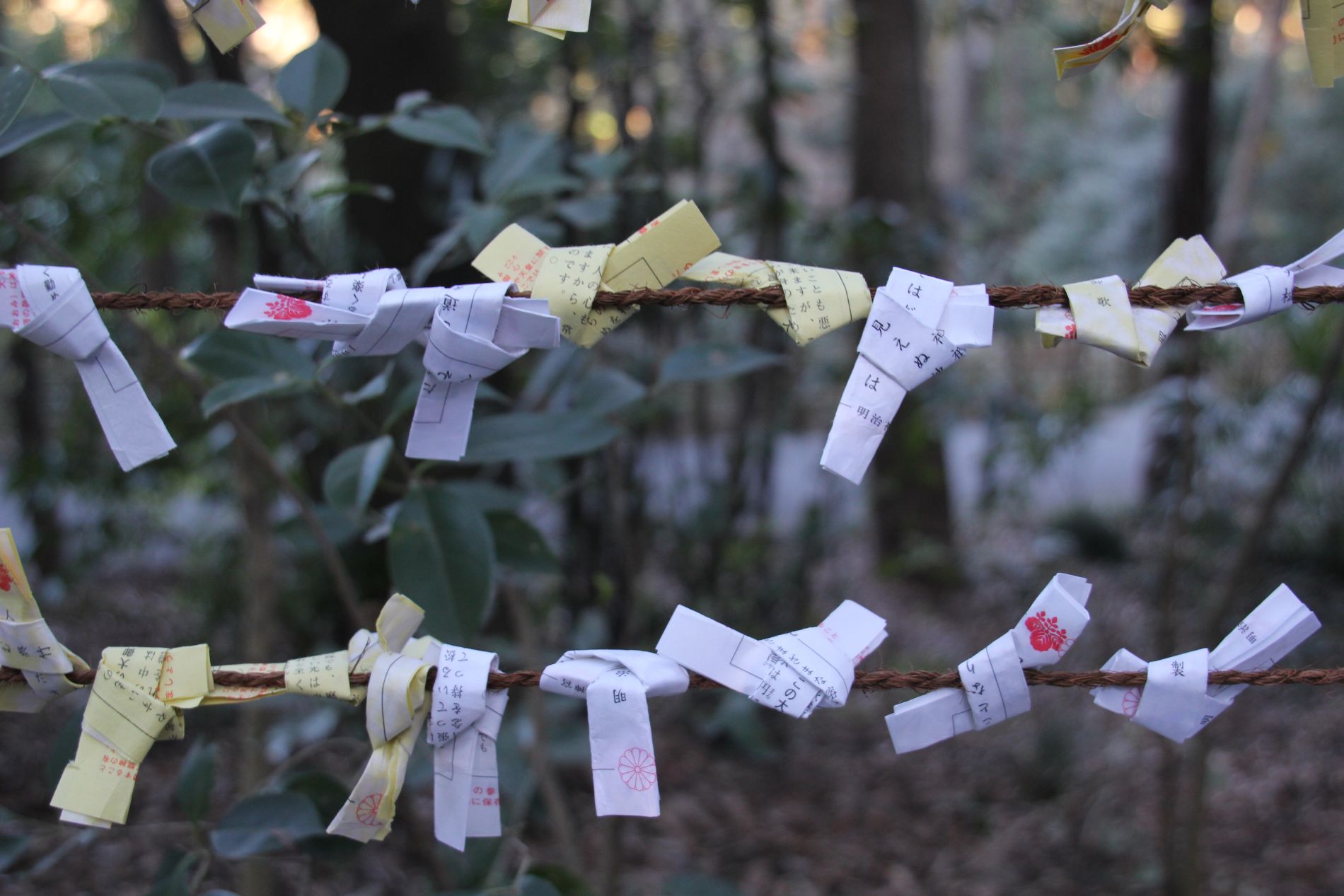

Folded omikuji hang from a wire fence.

“We tie bad omikuji to a tree or to these wires, so the bad luck doesn’t follow us,” she says. I look past her and notice thousands of Japanese shrine-visitors tying their fortunes to the fence.

Standing in the shrine, watching so many people leaving their bad omikuji behind, I find myself wondering why I’m seemingly the only person who has received a good fortune. How is it that I, the American inconvenienced by an ongoing mortgage crisis and economic recession, am getting looked upon so kindly by the Shinto gods? I feel guilty.

Three months later, I’m sitting in a bar in the Windsor Hotel in Cairo, Egypt, when I see a television with CNN reporting that the tsunami resulting from a magnitude 9.0 earthquake has destroyed towns across Japan and has caused the largest nuclear accident since the 1986 Chernobyl disaster.

I open my wallet and take out my omikuji, which I have been keeping there since January for good luck. There’s a moment where, more than anything, I wish I could travel back in time and give it to the friendly woman at Meiji Jingu Shrine.

How I became a Japanese teen heartthrob

Examining Japan’s obsession with cuteness.

SEPTEMBER 25, 2011 — Everywhere I look, I’m surrounded by cuteness. The colorful beverage vending machine outside my hotel demands that I push on a bunny’s head to make a purchase. The police station down the street has a statue standing near the door of Pipo-kun, an orange creature with blue hair which serves as the bizarre mascot of the Tokyo police. Boxes of chocolate éclairs adorned with pictures of panda bears and pigtailed children beckon me from stores as I walk down the street. Meanwhile, almost every girl who passes me is modeling some kind of Hello Kitty accessory. Even the subway train I took from Narita airport into Tokyo had a Pokémon character plastered onto the side, solidifying what friends had told me already before I arrived: the Japanese are obsessed with all things cute — also known as kawaii, in Japanese.

Manga characters overlook a busy street in Akihabara, Tokyo, Japan.

Now, I’m walking through Akihabara, a shopping district in Tokyo dedicated to computers, electronics, manga (Japanese comics), and anime (Japanese animated films). For otakus — the Japanese word for geeks obsessed with anime and manga — it’s a paradise. But, here, kawaii takes a turn toward the erotic. On the street, a girl wearing a short white and pink skirt and a headband with cat ears giggles and talks in a high voice with a group of men looking for a maid café — a restaurant in which waitresses, dressed in maid costumes, serve food and play board games to entertain male customers. Meanwhile, I wander through the maze of bookshelves and display cases at Mandarake, Tokyo’s famous superstore filled with used anime and manga-related products, overwhelmed by comic books adorned with scantily-clad teenage girls (known as hentai) and figurines of Japanese schoolgirls wearing micro-miniskirts.

Two Japanese girls dressed as maids with cat ears flirt with men near a maid cafe in Akihabara, Tokyo, Japan.

Like most men, I find sensual enticements titillating, but there’s a big part of me that feels uncomfortable here. There’s something unnerving about a world where the sexual ideal encourages people to look — and behave — as young and innocent as possible. The Japanese obsession with kawaii goes beyond the American obsession with youth; it’s not just enough to look cute. Both looking and behaving like a prepubescent, giggling and accessorizing with plush toys, is the ideal — and one not just limited to women. In 2007, the New York Times wrote that Japanese men also aspire to be skinny and cute, aiming to weigh about 125 pounds and fit into exceptionally slim clothing. So, when I jump on a train to Otome Road — a sort-of Akihabara for girls and women near Tokyo’s Ikebukuro Station — I discover a street crammed with stores catering to otome, the female equivalent of an otaku. Covers of anime DVDs and manga feature feminine-looking faces of young, teenage boys. Here, it’s clear that the sexualization of teenage boys isn’t off limits. As I continue to explore, I discover Swallowtail, a “butler café” where Japanese girls can order around a submissive but attractive young man who will serve them food and treat them like a princess.

A man browses adult manga (hentai) in the Mandarake store in Akihabara, Tokyo, Japan.

Curious about the attraction to these maid and butler cafés, I decide to visit a @Home Cafe, a maid café whose advertisement greets me with, “Welcome home, master!” and promises me an English-speaking waitress. Inside, the hostess squeals when she sees me and seats me at a counter. The café’s advertisements have significantly overpromised her English-speaking abilities, but she manages to tell me that I can look around and choose the maid to serve me whom I find most attractive. They all look like they’re about 20 years old, and I point to one who looks especially kawaii. She blushes, hurries over to me, and presents me with a ridiculous menu in Engrish that explains that, for a single price, she will serve me a drink, fried rice (“Your maid will draw a doodle on your rice!”), ice cream, and play a game with me. Even more thrilling, I learn that if I win the game, I’ll get a discount on my meal. I have no idea what kind of “game” I’ll have to play, but I’m already nervous.

People browse anime character pillow covers in the Mandarake store in Akihabara, Tokyo, Japan.

My maid spends a little time flirting with me and asking me questions in broken English about myself. Like the Vietnamese girls I met in at the top of the Pass of Ocean Clouds, she reacts to the fact that I live in California as though her favorite manga character just proposed to her. When she serves me my meal, she giggles as she draws a happy face on my fried rice using a ketchup bottle. When I try the food, I realize that this may be her subtle way of apologizing for the disgusting cuisine.

Fetish DVDs featuring women underwater are sold in Akihabara, Tokyo, Japan.

Once she’s seen that I’ve choked down most of my food, she bounces back over to me with a plastic crocodile with an open mouth full of teeth. Clearly, she doesn’t know the English words for crocodile or tooth (and, of course, I don’t know the words in Japanese), so she attempts to explain the game to me by grabbing one of my fingers and pushing it onto one of the crocodile’s teeth. Nothing happens, but she starts cheering and clapping as though I’ve just won the lottery. I’m bewildered. But, then, laughing and giggling, she pushes one of her fingers onto one of the crocodile’s teeth and the crocodile’s mouth slams shut on her finger. She feigns extreme disappointment and pouts while she marks a point for me on a notepad. When I put my finger into the crocodile’s mouth again, it slams shut, and she feigns sympathy as she gives herself a point. I feel like I’m six years old, playing games with the dumbest kid in my grade. There’s nothing about the experience that feels like a turn on.

A Japanese girl dressed as a maid waits on boys in a maid cafe in Akihabara, Tokyo, Japan.

Despite my excellent crocodile-dentistry skills, she manages to beat me at Crocodile Dentist, depriving me of a meal discount. She gives me an apologetic, pouting face that makes her look like she feels really, really bad for accidentally driving over my dog. As an apparent consolation prize, she puts rabbit ears on my head, demonstrates how I can make a heart shape with my hands, and has the restaurant host take a photo of the two of us together. With a pink marker, she draws a picture on the photo of a heart balloon above my head, writes my name in it, and then adds to the bottom of the photo: “♥ Thank you ♥ Hank.” Apparently, in the land of kawaii, hearts are an acceptable substitute for standard punctuation.

Japanese girls buy manga on Otome Road in Tokyo, Japan.

Though repression of sexuality is common in many cultures, it becomes clear, as I walk through Akihabra, that the complexity of repressed sexual desire in Japan is more manifest. Of course, there’s the women wearing maid costumes playing Crocodile Dentist and pornographic comic books, but as I wander into the dark corners of some stores, I also find hundreds of figurines of scantily-clad teenage anime characters, life-like love dolls, and perhaps most strange: DVDs for fetishists who like their cute girls underwater. (No, I don’t understand it either.) I even find multiple displays of anime character pillow covers, presumably purchased by men who, as described in the infamous 2009 New York Times article, hope to cultivate a romantic relationship with their pillows. Also adding to the complexity of the Japanese psyche, I see advertisements for Japanese hostess clubs, where hostesses pour drinks for and flirt with — but nothing more — the clientele. (Imagine a strip club without the stripping.) This, combined with the obsession with cuteness, gives me the distinct impression that the Japanese feel strangely threatened by adults exerting sexuality.

A cosplay girl browses for costumes on Otome Road in Tokyo, Japan.

Exhausted by Akihabara, I decide to escape the next day to squeaky-clean Tokyo Disneyland, a place where I expect asexual cuteness to reign. I feel silly visiting, considering that my apartment in Los Angeles is only a fifty minute drive from the original Disneyland, but I’m hoping that Japan’s obsession with kawaii will give Tokyo’s version a unique flavor.

Once inside, I’m a little surprised by the homogeneousness of the visitors; unlike the theme parks in California and Florida, which serve as destinations for tourists from all around the world, Tokyo Disneyland is full mostly with Japanese tourists. As I explore, I’m a little disappointed that the park is almost identical to Disney World, but I’m relieved to discover that it’s still “the happiest place on Earth.” I see Japanese tourists with expensive telephoto lenses photographing Mickey and Minnie Mouse dancing in a parade while wearing kimonos; I hear Splash Mountain’s “Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah” soundtrack in Japanese, and I watch Japanese families eat churros (delightful cultural dissonance!).

Minnie Mouse wears a kimono in Tokyo Disneyland.

The highlight of my day turns out to be a Jungle Cruise boat ride with a very enthusiastic boat skipper performing the funny (and ironic) Jungle Cruise script in Japanese. Tokyo Disneyland’s cast members, who are exceptionally enthusiastic and invested in the characters, make the park’s day-to-day operations feel like they’re a notch above their American counterparts. Hearing in Japanese the ride’s scripted jokes about the dangers of a cruise in a fake river and plastic, man-eating piranhas somehow makes them twice as funny. The boat passengers also seem to enjoy the skipper’s patter, especially a beautiful, elegant Japanese woman near my age who, I notice, is neither wearing any pink cat ears nor exhibiting any Hello Kitty products. I’m instantly attracted to her, significantly more than the girls on the covers of the Akihabara anime videos and the Crocodile Dentist-playing maid.

Women take photos of a parade at Tokyo Disneyland.

“Konnichiwa,” I say to her. She smiles politely and says something in Japanese, but I’m already out of Japanese vocabulary. I smile, but when she disembarks from the boat, she heads toward Space Mountain while I head toward the Pirates of the Caribbean.

While I’m standing in line for the ride by myself, trying to find a Japanese-English dictionary on my phone, I notice about ten teenage Japanese girls in front of me in line, looking back at me, pointing and giggling. Most of them avoid making eye contact with me, but one seems like she’s trying to a drill a hole through my head with her eyes. The world described by the famous Charisma Man comic strip — in which girls in Asian countries treat tall, blue-eyed guys like me as though they’re Johnny Depp — seems more spot-on than ever. She’s much too young for me, so, in an attempt to scare her away through embarrassment, I look directly into her eyes and give her a big smile. At first, my strategy works; her face turns red and she immediately turns away, giggling and gossiping loudly with her friends. But, within a minute, she continues staring at me while her friends continue to laugh. I focus my attention on learning more Japanese vocabulary.

A Japanese family eats churros in Tokyo Disneyland.

But, when I get to the front of the line, an especially efficient, piratey Disneyland cast member directs me to the front seat of a boat. When I look up from my phone, I see that the pirate has filled the back of the boat with the group of giggling Japanese girls. I can only assume that the girls requested this arrangement specifically, because I can’t imagine that any pirate would inflict this on me intentionally. Soon, I’m floating through a Louisiana bayou to the sound of banjo music with ten teenage Japanese girls imagining they’re on a romantic Disneyland date with me. It’s awkward.

A young Japanese girl looks at Cinderella’s Fairy Tale Hall in Tokyo Disneyland at night.

As our boat leaves the bayou and begins climbing toward the ride’s first drop, the girl who couldn’t stop staring at me in line taps me on the shoulder.

“Where. are. you. from?” she slowly coos in a high voice with an innocent smile. I brace myself.

“I’m from California,” I respond.

I’m not surprised when the entire group of girls claps and cheers. They’re all wearing pink hair bows or plastic mouse ears or carrying Hello Kitty purses. They’re really cute.

“You could be a movie star,” the girl says to me.

I’ve become a Japanese teen heartthrob.

But, even in a world ruled by cuteness, I’m still thinking of the elegant woman with whom I shared a Jungle Cruise boat. I didn’t hear her giggle once.

How to Visit Tokyo’s Meiji Jingu Shrine

OVERVIEW: Tokyo’s most respected Shinto shrine, Meiji Jingu opened in 1920 in honor of Emperor and Empress Meiji, thought of at the first modern leaders of Japan. The country’s two largest torii (entry gates) serve as the entrance to the shrine.

LOGISTICS: Fly to Narita International Airport, then take the Narita Express train (55 minutes, US $38) or the Airport Narita train (80 minutes, US $17) to Tokyo. From there, take the Tokyo subway’s JR Yamanote Line and get off at Harajuku Station. Upon exiting the station, it’s just a short walk into Yoyogi Park and the shrine.

ENTERING AND EXITING: Start by bowing once when entering and again when leaving at the shrine’s torii (a large wooden gate).

RINSING: At the shrine’s temizuya (a stone wash basin), start by rinsing your left hand, followed by your right hand. Second, pour water into your left hand and use it to rinse your mouth. Third, rinse your left hand again, and then rinse the water dipper. The water dipper should never touch your lips.

PRAYING OR MAKING A WISH: Start by ringing the bell that hangs in front of the offering box (though some shrines, including Meiji Jingu, do not have a hanging bell). Next, throw coins into the wooden offering box. Then, bow twice, clap your hands twice, pray and/or make a wish, and then bow once more.

How to Visit Akihabara and the @Home Maid Cafe

OVERVIEW: While Tokyo’s Akihabara neighborhood is still a big part of Japan’s legendary electronics industry, it’s now even more focused on the booming cartoon anime and manga markets. The neighborhood is filled with girls in costumes advertising maid cafes, restaurants in which waitresses, dressed as maids, serve food and play board games to entertain male customers.

LOGISTICS: From Tokyo, take the subway’s JR Yamanote Line and get off at Akihabara Station.

MAID CAFES: Maid cafes are advertised everywhere in Akihabara. I visited the @Home Maid Cafe on floors 4-7 of the Mitsuwa building on the corner of Chuo St. and Kanda-mykoin St.

ANIME AND MANGA: Be sure to visit at least one of Mandarake, Animate, Book-Off, or K-Books, where you’ll find hours of entertainment looking at the enormous variety of anime, manga, and related products.

How to Visit Otome Road

OVERVIEW: Girls interested in anime and manga should visit Otome Road, where female anime and manga fans go to get their fix. Note that there isn’t a road actually named Otome — the business district is located west of the Sunshine 60 building near Ikebukuro station.

LOGISTICS: The easiest way to find the area is to find the Ikebukuro Animate store, at 3-2-1 Higashi Ikebukuro, Toshima-ku. From Tokyo, take the subway’s JR Yurakucho Line and get off at Higashi-Ikebukuro Station.

How to Visit Tokyo Disney Resort

OVERVIEW: The Tokyo Disney Resort, which includes two theme parks, Tokyo Disneyland and Tokyo DisneySea, was the first Disney theme park resort to open outside of the United States. Tokyo Disneyland’s attractions and layout are nearly identical to those at Disney World Resort’s Magic Kingdom, but Tokyo DisneySea’s attractions are almost all unique to Japan except for the Tower of Terror and Indiana Jones Adventure.

LOGISTICS: After flying to Narita International Airport, the cheapest way to get to Tokyo Disney is to take the Airport Narita train (80 minutes, US $17) to Tokyo Station. Then, take the subway’s JR Keiyo Line or JR Musashino Line to Maihama Station (15 minutes, 210 yen, US $3). It’s a very short walk from Maihama to the Resort, and you’ve only spent US $20. If you’re willing to spend a little more, a direct bus is available from Narita airport (60 minutes, 2400 yen, US $31) and other buses are available for 700 yen (US $9) from various stations in Tokyo.

TICKETS: Tokyo Disney Resort tickets can be purchased in advance on its web site. Adult tickets for the Tokyo Disney Resort cost 6,200 yen/US $81 for one day, 10,600 yen/US $138 for two days, or 13,800 yen/US $180 for three days, but visitors are not permitted to enter more than one of the two theme parks on the same day. On selected evenings, evening-only tickets are available for 4,900 yen/US $64.

Wow Hank. That was a really poignant end to the story. As always, great article….

i can’t stop laughing. when i lived in japan, i often felt like a movie star. 🙂 white tall redheaded female? yep. you nailed it! 🙂

Crazy turn of events. Very interesting. I love your candid approach. Plus, your reflections after the Tsunami left me with tears in my eyes.

I happen to be half Japanese so due to that I visit Japan every summer to see my family there. I must say that I can share sympathy with the teenage girls because I have never seen any attractive men there who aren’t over 20 XD and whenever I come back I feel like there are some guys who are under appreciated 🙂 But the good thing about Japan is that there’s something there that will please anyone 😀

It’s funny. I’ve lived the otaku life. When I was in middle school I was obsessed. It was naiive. I had money to spend and ended up buying more then 5000 worth of lolitas, manga, anime, and con novelties. I grew out of it, but I want to learn about why Japan is obsessed with innocence and why America is obsessed with it. I truly enjoyed your paper and pictures. It’s strange to relive the culture.

i enjoyed reading this. found myself smiling. i happen to like japan because of their cuteness. thanks.

I laughed so hard I cried. Thanks!