DECEMBER 12, 2010 — “I’d like to buy a train ticket to Agra,” I tell the clerk in the foreigners-only ticket office in the Delhi train station. He and four twins sitting beside him are wearing long, white coats that make them look like they will be able to solve any of my medical problems — as long as those problems, of course, are train-ticket related.

“What train number?” Doctor Train Ticket asks me, annoyed.

“I don’t know the train number,” I explain. This is my first Indian Railways experience, and I’m totally clueless.

“It is not my job to tell you the train numbers,” he says. “You must go to the Enquiry Desk.” But isn’t that where I am? I wonder. Between me and Doctor Train Ticket sits a computer — 1984’s flagship model — that could surely solve all of my problems.

“Can’t you just look up the number for the next train to Delhi on your computer and put me on it?” I ask. Doctor Train Ticket acts like I’ve just asked him to cure cancer on the spot — which I’d expect him to be able to do, considering his jacket. Well, at least he should be able to cure train cancer. Visibly angry, he spends a few minutes typing cryptic commands into his computer. This guy has never heard of Windows 7 or MacOS.

“The next two trains to Delhi leave at 1:30 and 2:30, but I can only book trains four hours before they are scheduled to leave,” he says. “I can book the 5:30 train for you.” It’s 11:30 in the morning, and Doctor Train Ticket seems absolutely thrilled that he’s just ruined my entire day with a few keypresses.

Men inexplicably wearing white doctor coats man the foreigners-only ticket office in the New Delhi train station.

“No, I want to go on the next train. Can’t you put me on it?” I ask, exhausted.

“You can only book those at windows 61 to 66, downstairs,” he says. Of course, I think. I should have known. I start to realize that there might be a huge market demand for an Indian Railways Bureaucracy Idiosyncrasies for Dummies book. I consider writing it.

Downstairs, surrounded by hordes of frantic Indian travelers, I wait in line at window 64 for about 20 minutes. Indians repeatedly push me out of the way and cut in the “line” (which is more of a mass) in front me of me until I begin to defend my territory. When I finally reach the window, I fill out a ticket purchase form, which asks for my name, address, age, and an assortment of other information totally irrelevant to riding on a train. I don’t write anything after “Train Number” and hand it to the man at the window.

“Number?” The clerk on the other side of the glass looks at me with challenging eyes. This one’s not wearing a doctor’s coat.

“I don’t know the number! Please, just put me on the next train to Agra,” I say. I’m almost ready to hijack any train to Agra.

“STOP. RED. STOP! RED!” the clerk exclaims obtusely. Apparently, only Delhi train station employees with Train Ticket Doctorates and accompanying white coats can speak coherent English.

“Red?!” I ask, looking at him with a blank stare. He turns his computer screen toward me so I can read an English error message: “CHARTING IS FINISHED; TWO HOUR TICKET BOOKING WINDOW NOT OPEN.”

“RED!” he shouts. Apparently there’s a two hour window at the beginning of the four hour window before an Indian Railways train leaves during which no one can buy a train ticket. But, then, I realize that it’s already noon, and I already am within a two hour window of the 1:30 train’s departure.

“But it’s noon!” I try to tell the clerk, realizing quickly that I’m wasting my time. After all, “CHARTING IS FINISHED.” Or something.

“RED. Wait,” he says, and motions for me to step aside.

I stand next to the clerk’s window for over an hour, checking with him every 10 minutes to see if the mysterious purchasing window has opened.

Passengers flood the New Delhi train station.

“RED!” he repeats, over and over. Strangely, I find myself missing Doctor Train Ticket, who I never liked, but at least he knew English words other than “red.” Eventually, with only 10 minutes before the train’s departure, it becomes clear that “RED!” is never going to become “GREEN!” Then, I remember a tip from an India travel connoisseur I met while traveling.

“Can you just sell me a General Ticket on the train to Agra?” I ask. General Tickets don’t give buyers assigned seats, but they can be upgraded on the train by speaking with the conductor.

“50 rupees,” he says. I pay him, and he hands me a ticket. I sprint to one of the train’s 3AC cars — Indian trains usually have an assortment of classes: Second Class, First Class, Sleeper, 3AC, 2AC, and 1AC. Second Class and First Class have seats, Sleeper has beds without bedding or air conditioning, and the three air-conditioned classes have beds (with blankets) that progressively become less congested the more money a passenger pays.

I literally run into the conductor on the way to the train. He’s not wearing a doctor’s coat but his conductor’s uniform makes him look official enough.

“What can I do with this ticket?” I ask him. “Where’s the best place I can sit?”

He motions for me to follow him into a 3AC car and points to an upper bed.

“I can upgrade you for 70 rupees.”

“Done,” I say. He writes me a replacement ticket — Indian businesses seem to love handwritten paperwork more than anything in the world (hotels often provide me with two or three written receipts). I climb over people sitting on a lower bunk and settle into my berth. Finally, I’m on my way to the Taj Mahal.

Well, actually, the train departs 40 minutes late. Maybe Doctor Train Ticket wasn’t finished charting.

Entranced by the world’s most beautiful symbol of eternal love

Sunrise and sunset at the Taj Mahal.

DECEMBER 17, 2010 — As soon as my train to Agra leaves from Delhi, I find myself confused again. I’m lying on my reserved upper berth, though most of the train car beds aren’t being used and almost all of the passengers are sitting on lower seats. I feel ridiculous, like I’m emperor of my train car, overseeing the rest of the passengers from above. Meanwhile, men pass by below me, offering a mysterious vegetarian curry out of industrial-sized buckets. I motion for one to serve me some on a paper plate, but when I try to pay for the food, he won’t accept any money. This is the first time I’ve gotten anything for free in India. I conclude that the food is going to kill me.

An Indian couple is entranced by the view of the Taj Mahal at sunset from Mehtab Bagh Park in Agra, India.

While I’m eating, the train makes a stop and passengers disembark, but the conductor makes no announcements. I can’t see through any of the train’s tiny lower windows from my upper bunk. I have no idea where I am.

“Is this Agra?” I ask a man sitting below me. I ask as nicely as possible, in an attempt to avoid appearing as a self-righteous train car emperor, shouting questions to my serfs. After all, I remember, Taj Mahal-builder and Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan was overthrown by his son soon after the Taj Mahal’s completion. The man below shakes his head and, in Hindi, I think he tells me that we still have a long ride to Agra. Another man walks by selling non-vegetarian food in foil tins. The first shots of an intestinal war have already been fired as a result of my free bucket food, so I decline. As the train chugs toward Agra, stopping at stations along the way, I find myself continuously recruiting new serfs below me to keep track of where we are. By the time I’m halfway through the journey, I have an eighteen year old kid, two Indian soldiers, and a young woman — none of whom can speak English — trying to assist me. It’s easy to accidentally aggregate helpers on the train; mercifully, Indians tend to be especially protective of clueless Westerners trying to make sense of Indian public transportation. At one point, the two Indian soldiers demand that a teenager move his feet resting on my berth, and the young woman makes food recommendations as buckets whisk by. They’re kind of like four Train-Fairy Godmothers. Soon, I fall asleep.

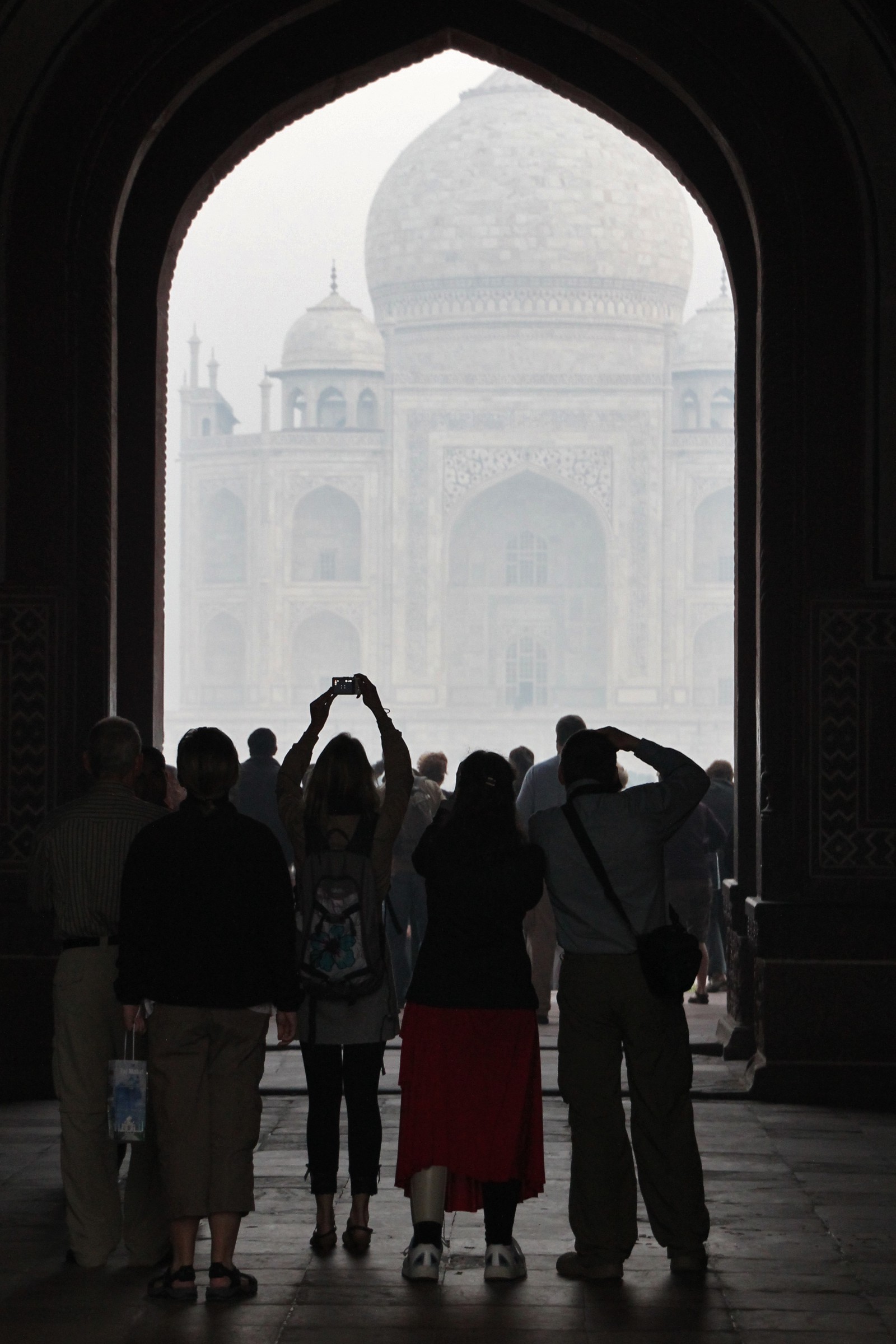

Tourists photograph the Taj Mahal through the complex’s Great Gate at sunrise.

Suddenly, I awake to the sound of four Indians chanting “Agra! Agra!” in unison. I abruptly end my time as train car emperor, jump down from my bed, thank the four of them, and catch a taxi to my Agra guesthouse. Before he leaves, I arrange for my taxi driver to pick me up at 6 AM the next morning to take me to the Taj Mahal.

In the morning, I tell my driver to take me to the East Gate of the Taj Mahal. He promptly takes me to a roundabout near the West Gate instead — though his “East Gate!” announcement upon our arrival is quite convincing. India’s perpetually dishonest taxi drivers always have ulterior (and sometimes mysterious) motives; in this case, he was trying to save gas by taking me to the Gate closer to my hotel and, according to Lonely Planet, possibly collect a kickback from camel and rickshaw drivers sitting near the West Gate waiting to take tourists to the Taj’s ticket office. I don’t bother to argue with him since there’s not much time until sunrise, and I walk quickly to the entrance. Standing in line with about twenty other mostly Indian tourists, I’m surprised to see a lack of Westerners — I imagined that every white person in India would be flocking to the Taj Mahal.

A couple gazes at the Taj Mahal from the bank of the Yamuna River.

Finally, the doors open, and I catch my first glimpse of the building considered to be the most beautiful in the world, one whose creator boasted that it made “the sun and the moon shed tears from their eyes.” I see the famous white, marble dome peeking through the arch of the Great Gate as tourists hold cameras high above their heads to get their first snapshot. I walk deliberately toward and around the Taj, soaking in the dawn, slowly taking photos from every possible angle. A handful of photographers gather in front of the adjacent Taj Mahal mosque with me to capture the sun as it rises behind it. Everyone is reverent, taking care not to interfere with others’ photographs and offering to help take posed pictures. The moment is perfect for the photographer gaggle: mist blankets the Yamuna River behind the structure, and the building looks like it has risen spontaneously from a clouded heaven, a concrete manifestation of nirvana.

The sun rises behind the Taj Mahal.

The simple presence of the Taj, built as a symbol of eternal love by Emperor Jahan in memory of his third wife who died during childbirth, seems to encourage even rabid photographers to cooperate with each other.

I spend almost two hours touring and photographing the Taj, walking around its walls, admiring the calligraphy on the entrance arch, gazing at the minarets, and touching the intricate lattice screens in the mausoleum interior. I’m just about finished, taking a few final classic Taj Mahal reflection pool photographs from outside, when a beautiful, young blond woman performing playful, provocative poses for her friend’s camera catches my eye. Soon, a string of Indian men, and some Indian families too, start interrupting to ask her to pose with them in souvenir photos.

Calligraphy on the Taj Mahal

“The Indian tourists seem more interested in your white skin and blond hair than the white marble of the Taj Mahal,” I say to her. “I’m pretty sure a lot of these Indian guys are leaving with more pictures of you than the Taj.”

She chuckles and introduces herself to me as Sophie, from France, and, quickly, we’re trading funny stories of our travels through India. We like each other immediately. We find ourselves chatting in front of the Taj’s reflection pool for about a half hour as Indian men gawk at us. But when Sophie and I realize that we’re headed in opposite directions — she toward Amritsar in northern India and me toward Kerala in southern India — we share an awkward moment during which we realize that this is the one and only meeting of our entire lives.

“Well, it truly has been a pleasure, Hank,” she says. Her eyes hold on mine. For a long moment, she doesn’t look away. I can’t tell whether she’s staring at me or at the exquisite reflection of the Taj Mahal in the pool behind me.

She walks past me, in front of the rising sun. Then, she glances back at me one last time, smiles, and then shifts her gaze, once again, toward the world’s most beautiful symbol of eternal love.

To cushion the blow of saying goodbye to the Taj and Sophie, I ask a taxi driver to take me to India’s best hotel, the Oberoi Amar Villas, for breakfast. The driver takes me to two other hotels first and tries to convince me that they’re the Oberoi, in hopes of getting some hotel kickbacks. But his standins look like concrete boxes, whereas I know that the Oberoi is a dazzling palace, and his ruses fail. When I finally walk into the Oberoi, I feel like I’ve walked into ancient history and have become an emperor: the air is jasmine-scented, the architecture is lavish, and the staff, dressed like royal Mughal servants, provides impeccable service. After a huge meal of Eggs Benedict and French toast, I decide to visit the rest of the sights in Agra. But I find myself still thinking about Sophie and the Taj Mahal. At sunset, I ask a taxi driver to take me to Mehtab Bagh, a park that sits immediately across the Yamuna River, to see the Taj one last time.

A woman photographs the Taj Mahal from the tip of the garden’s reflection pool.

From across the river, I watch the sunset as it casts a fantastic orange glow on the Taj’s white dome. I imagine Sophie, again, in front of the Taj, but, of course, she is nowhere to be found.

As dusk falls, birds fly overhead and I see an oarsman paddling a small canoe with a group of people down the river, in front of the Taj. I watch two teenage Indian couples, embracing on a brick wall, entranced by the view.

They can’t look away. Neither can I.

How to See the Taj Mahal at Sunrise and Sunset

OVERVIEW: The Taj Mahal — and many other beautiful sites, including Agra Fort, Akbar’s Mausoleum and Itimad-Ud-Daulah (the Baby Taj) — are located in Agra, Uttar Pradesh, which is a two- to three-hour train ride from Delhi. The Taj has a steep entry fee (750 Rs/US $17), but, hey, it’s the most beautiful building in the world. Your Taj ticket can be used to get discounts on tickets for most other attractions around Agra.

LOGISTICS: Fly to Delhi and ask a taxi driver to take you to the New Delhi train station to take a train to Agra (370 Rs/US $8 or 700 Rs/US $15 for a bed in 1AC), which is the easiest and fastest way to get there. You can also fly directly to Agra from Delhi for about 4,500 Rs (US $100) or take a bus (120 Rs, 4.5 hours). The notoriously dishonest taxi drivers in Delhi (and throughout India) will try to overcharge you, tell you that your hotel has burned down so they can take you to one that will pay commission, drop you at a commission-paying store instead of your destination, or bring you to a fake (but genuine-looking) tourist office where you will be told that the only way to get to your destination is by hiring an expensive car and driver. Be aware and don’t fall for any of it. At airports and train stations, try to use only pre-paid taxi stands, which can help minimize (but not eliminate) these shenanigans. If all else fails, threaten not to pay a driver or report him to the police — doing either usually fixes most problems.

TRAVELING BY TRAIN IN INDIA: Despite my chaotic ticket-buying experience at the Delhi train station, traveling by train in India can be one of the fastest and most inexpensive ways to travel if you can figure out the rules. If you have time to book your train at least four hours before it leaves and you want to book any AC class, use the convenient Cleartrip to look up itineraries, then book and print your ticket online. Cleartrip charges a service fee of about 25 Rs (55 US cents) per ticket, so, for cheap tickets, you may prefer to book at a station. To do this, go directly to the station’s Current Booking window within a two hour window before your train departs, fill out a request form, and you’ll have your ticket quickly if assigned seats are still available. To help with train numbers, use Cleartrip online, or buy the handy Trains at a Glance, which contains the entire Indian Railways schedule, at any train station bookstore. Book a General Ticket and ask a conductor for an upgrade on the train if no seats are available. Of course, at the hectic Delhi train station, tourists can use the foreigners-only booking office, labeled “International Tourist Bureau,” on the first floor of the station’s main building. (If you can’t find it, ask a railway official; there is at least one unofficial and misleading tourist office, and finding the official one is difficult if you’re on the wrong side of the station. I guarantee that it’s not closed and it hasn’t burned down.)

SEEING THE TAJ MAHAL AT SUNRISE: Once you’ve landed in Agra — whether by train, bus, plane, or car — arrange for the driver who takes you to your hotel (it’s best to arrange in advance for your hotel to pick you up to avoid scams) to pick you up before sunrise the next morning to take you to the Taj. Haggle. Demand to be taken to the Taj’s East Gate — otherwise, taxi drivers will take you to a roundabout far from the West Gate, which can be a long walk (or expensive camel/carriage ride) and crowded. The East Gate also has the advantage of being near Oberoi Amar Villas, possibly the best hotel in India, to which you’ll want your driver to deliver you for breakfast after your Taj visit. Spend a couple hours soaking in Emperor Shah Jahan’s monument to eternal love; by 9 AM, the complex will be swimming with tourists.

SEEING THE TAJ MAHAL AT SUNSET FROM MEHTAB BAGH PARK: In the evening, you may want to see the Taj one last time before leaving Agra. You can visit it again with the same entry ticket, or you can visit Mehtab Bagh (100 Rs/US $2), a park across the Yamuna River that has an exceptional view of the Taj. If you’re feeling extra adventurous, it is easy to sneak into the side of this park for free. You’ll see lots of Indian couples enjoying the sunset view of the Taj before darkness falls.

Your writing is always very expressive, Hank, and I have to say that this piece is my favourite. It makes me want to get on a plane to India right this minute!

this is really helpful while I’m planning for visit Taj.

breakfast at Oberoi after visit Taj? I like this idea.

So .. did you never hear from sophie again? so tragic.

I will visit the Taj sometime this year. I so eager to…

No, meeting Sophie was a one time thing, unfortunately!

You’re writing is so interesting. I came across your blog through a google search on men’s wearhouse lost and found :p but you’re writing has me here for a while…thanks! 🙂

Ha! Sounds familiar! Although the men were ‘clicking’ their mouths at me instead of shouting… still don’t know what that was about! All adds to the flavour of the country though 😉 I was there booking a last-minute ticket as my train was 24 hours late & I’d already had to sleep overnight in the cold, on the platform by myself; but after pushing and glaring my way to the desk, I eventually got a ticket on a train which allowed me to stand by the door for the 5 hour journey… Got worse after that, but still, was an experience! 🙂

I fell in love with your love story. I hate the ending… grrr! lol.. To see Taj Mahal is a dream. So my wife and I will be heading to Agra a few days from now!.. we love your page Hank!